Sensory Integration and Bathing: Evidence and intervention strategies to help bridge the gap

Bathing is a Sensory Experience

Bath and Shower time can provide a variety of sensory experiences that can be fun and can help support the bedtime routine. However, for a child/individual with sensory sensitivities, this activity can be emotional and anxiety provoking.

Those with postural or motor planning difficulties may feel insecure sitting and moving around the bath. An over-responsive individual may not like the feel or sound of the water and may even interpret these as alarming or threatening making the whole experience very intense. This can be overwhelming resulting in them refusing to engage in this self-care task.

Sensory Processing and Bathing

There are three main sensory systems affected by bathing.

Tactile System

The tactile system dictates how we interpret the information we get from the receptors on our skin.

It helps us understand:

- Temperature differences

- Pressure

- Pain

- Textures

- Touch

Vestibular System

The vestibular system refers to the development of eye movements to track objects and structures within the inner ear that detect movement and positional changes of the head.

Difficulties present in either:

a. Hypersensitivity is when a person has fearful reactions to ordinary movements. Exaggerated emotional reactions could be instigated by surfaces that are uneven or unstable for example or climbing into a bath.

b. Hypo-reactiveness is when someone seeks intense sensory experiences. For example, excessive whirling, jumping, and spinning. This individual may put themselves in danger of a slip, trip or fall through excessive and unpredictable sudden movements.

Proprioceptive System

The proprioceptive system provides a person with subconscious awareness of the body’s position. Common signs of proprioceptive dysfunction include:

- Clumsiness

- A tendency to fall / unsteady on the feet

- Lack of awareness of body positioning in a small space

- Difficulty manipulating small objects

Step by step Analysis of Bathing – An important clinical reasoning tool for evaluating occupational performance:

- Turn on water to proper temperature – determines hot versus cold

- Hear water running – auditory system tolerates the sounds of running water

- Wash body – tolerates tactile input of soap

- Smells shampoo or soap – olfactory system tolerates the smells of shampoo and soap

- Use wash cloth – tolerates tactile input on skin of wash cloth

- Leans head back to wash hair – vestibular system tolerates head being tilted back

- Wash hair – tolerates water on head and over face

- Wash face – tolerates tactile input to face and closes mouth to avoid soap in mouth (sensation of taste)

- Towel dry – tolerates the feel of the towel over the body

Literature and Sensory Processing

Dunn, Winnie PhD, OTR, FAOTA Supporting Children to Participate Successfully in Everyday Life by Using Sensory Processing Knowledge, Infants & Young Children: April 2007 – Volume 20 – Issue 2 – p 84-101.

There is an accumulating amount of literature describing sensory processing in young children and suggesting the importance of this knowledge for understanding the characteristics of vulnerable children. This was carried out by Winnie Dunn.

Professionals and families need a working knowledge about sensory processing because it enables them to understand and interpret children’s behaviours and to tailor everyday activities so that children may have successful experiences. This article reviews Dunn’s model of sensory processing.

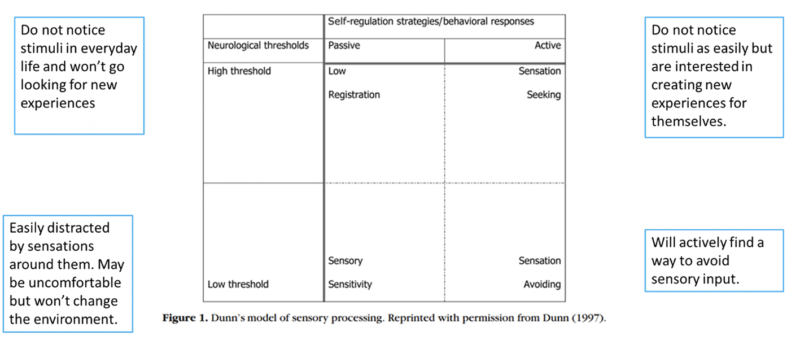

Dunn and her colleagues tested the relationship between a person’s nervous system and self-regulation strategies with different age groups, and in groups with and without specific disabilities. They looked at how the interaction of these functions creates four basic patterns of sensory processing. The result was that the patterns occur in each age group from infancy to adulthood and people with disabilities have both more distinctive and more intense patterns of processing than those without disabilities.

Sensory processing knowledge is useful for planning interventions that support children to have successful experiences in everyday life.

This article has 3 parts. First (A), there is a review of Dunn’s model of sensory processing. Second (B), the article presents behaviour patterns that would be associated with the 4 patterns of sensory processing in Dunn’s model. Finally (C), there is a discussion about how to apply sensory processing to intervention planning within different performance areas.

Dunn’s Model of Sensory Processing (1997)

This research was based on data from more than 1000 children with and without disabilities, Dunn hypothesized that there is a relationship between a person’s nervous system operations and self-regulation strategies, and that the interaction of these functions creates 4 basic patterns of sensory processing. What they found is that these patterns occur with people with autism, ADHD, developmental and learning disabilities have more intense patterns of sensory processing than do their peers without disabilities.

We all have sensory thresholds. A “threshold” is the point at which there is enough input to activate. When a stimulus is strong enough to trigger the threshold, it causes activation (i.e., you notice it). When a person has low sensory thresholds, this means that the person will notice and respond to stimuli quite often because the system readily activates to those sensory events (think of the cup analogy). When a person has high thresholds, this means that the person will miss stimuli that others notice easily because the system needs stronger stimuli to activate. For example, a person may easily notice what is happening around them.

Secondly it is important to understand self-regulation. At one end of the continuum, persons have a passive strategy; they let things happen around them, and then react. For example, a child may become irritable in the bathroom listening to the water fill up in the bath. It is a passive self-regulation strategy to remain in this environment even when the child feels uncomfortable from all the sounds. At the other end of the continuum, persons utilize an active strategy; they tend to do things to control the amount and type of input that is available to them. For example, the same child in the bathroom may move to a quieter place when the sound got overwhelming. It is an active self-regulation strategy to adjust one’s position to get a more manageable amount of sensory input.

Patterns of Sensory Processing

Sensation seeking:

They use active self-regulation strategies. They derive from sensation in everyday life. For example, they will look for physical movements such as twirling, swinging, climbing and bouncing. Sensory seekers will also look for additional sensory experiences for themselves, like humming or other mouth noises.

Low Registration:

In this sensory pattern, people do not notice sensory events in daily life. They are the passive response category. They may seem oblivious to their environments and may seem unresponsive. They may not notice when if they have washed the shampoo out of their hair or the soap off their bodies.

Sensory Sensitive:

People in this sensory pattern are easily distracted by sounds, movements, or smells such as in class or in the market. They may feel discomfort with certain textures of a sponge or soap. This high rate of noticing and continuing to experience all of these is a passive responding strategy.

Avoiding:

The people in this pattern will find different ways to reduce sensory input throughout the day. They use an active response strategy, meaning they would purposely try to avoid sensory input. As an example, they would not want to have their hair washed or have their teeth brushed.

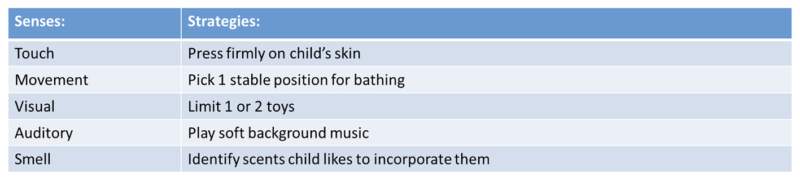

Applying Sensory Strategies

According to research conducted by Dunn, Winnie There is a discussion about different strategies that could be used for intervention planning within environments.

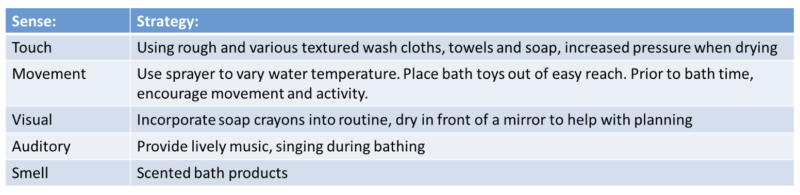

With more intensity of sensory input, these children can pay attention a longer time during daily life activities. The table provides some ideas for enhancing the sensory experiences during daily life activities.

Strategies for Children who miss bathing cues (low registration)

Case Study for low registration during bathing tasks

Rachel* is a 4 year old girl whose mother is frustrated with getting her awake, dressed and bathed in the morning. Her mother has to make several attempts to get Rachel awake, and because she is not alert, she does not actively participate in getting her clothing on and bathing. Observations and using the Infant/Toddler Sensory Profile data, the therapist determined that Rachel was missing a lot of cues in her environment (i.e., was experiencing low registration).

During the next visit, which was during Rachel’s wake-up time, they tried some of the suggestions. They opened her shades and turned on the radio, they selected brightly coloured and textured clothing. During bath time various textured soaps and bath toys were used as well as scented bath products. The OT also suggested placing different clothing items in different locations around her room to encourage movement and increase overall alertness during her morning routine.

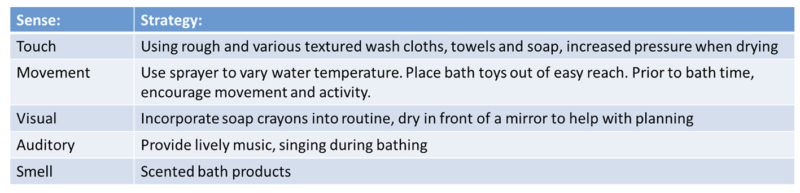

Strategies for children to provide opportunities to create sensations in everyday life (seeking)

More intense responses in seeking means that children enjoy sensory experiences and need more sensory input. The children’s interest and pleasure with sensory events might also lead to difficulties with task completion because they may get distracted with new sensory experiences and lose track of daily life tasks. With more opportunities for sensory input, these children can continue to pay attention during ADL’s.

This provides some ideas for enhancing the sensory experiences during bathing activities. You will notice that some of the ideas in this table are similar to the previous table this is because both “low registration” and “sensation seeking” are high thresh old patterns, which means that they need a lot of extra input to understand what sensory experiences are occurring.

Case Study for seeking behaviours during bathing tasks:

Frank* is a 4-year-old boy. His father is having difficulty getting through bath time successfully. The therapist meets with Frank and his father during bath time. Frank has many toys in the tub and seems to go from one to another. He enjoys being in the bath and is frequently trying to move about in the tub.

The Infant/Toddler Sensory Profile data confirm the therapist’s hypothesis that Frank is seeking sensations. The therapist and father make a schedule for the bath-time activities and place a laminated copy of the schedule on the bath wall. His father will mark off the activities as they complete them during bath time. The therapist brought some scented bath products, soap crayons, with additional items to increase the intensity of sensory experiences, and a focused plan for implementing the activities. Frank therefore gets more sensory input that is organized to facilitate completing the bath task successfully.

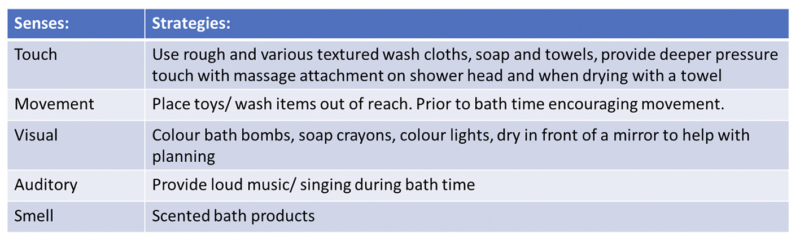

Strategies for supporting children who move away from sensations in everyday life (avoiding):

When children have a more intense response in sensation avoiding, this means that they notice things much more than others. Because these children notice more, one might observe that they are more isolated and are anxious more quickly. When environments are too challenging, these children may withdraw, and therefore not get activities completed in daily life. In general, these children will be better able to participate in everyday life activities when there is less sensory input available in the environment.

Case Study for avoiding behaviours during bathing tasks:

Miley* is a 6 year old girl. Her parents and day care provider is concerned about her play behaviours. At home, Miley seems content to play in her room; she has certain toys she plays with repeatedly and does not approach others to play. The Infant/Toddler Sensory Profile indicates that she tends to avoid sensations, particularly touch and sounds. The therapist explains that she seems to be getting overwhelmed by lots of sensations that occur during this open play time. For example, she can get bumped easily by other children and their toys, so hanging back and watching keeps her from having these unpredictable touch experiences. As bathing was a problem too in terms of the sound, the bath is now drawn before calling Miley and unscented soaps are used. Bath time has also been structured at a certain time each day so this is predictable and she feels prepared.

Strategies for supporting children who react quickly to situations (sensitivity)

With more structure regarding the sensory input that is available, these children can continue to pay attention during activities, and therefore stick with them for a longer time. Table 4 provides some ideas for managing the sensory experiences during daily life activities. You will notice that some of the ideas in this table are similar to Table 3; this is because both “sensation avoiding” and “sensory sensitivity” are low threshold patterns, which means that children may respond to input quickly and can get overwhelmed.

Case Study for children who are sensitive to bathing tasks:

Luke* is a 2-year-old boy who is a very picky eater. He is also sensitive to sensations related to his mouth and face. First, the therapist identified the characteristics of acceptable foods, including taste, texture, temperature, wetness, and colour. Understanding the characteristics of current meal choices provides a means to introduce a new food substance that has all the characteristics that Luke has accepted in the past, adding one new characteristic. Luke also did not enjoy getting his face wet during bathing tasks. A bathing visor was used during hair washing and when washing his face, firm movements and pressure was used with a soft sponge.

These examples of individualised intervention planning in the child’s daily routines show the impact that sensory processing knowledge can have on participation. Although there are many ways to interpret children’s behaviours, a sensory processing perspective adds helpful information. Since sensory processing knowledge is emerging from research, it also provides a means for designing evidence-based interventions as well.

In summary Dunn said that sensory processing knowledge has developed more over the last several years. Evidence indicates that both children and adults with and without disabilities exhibit 4 basic patterns of sensory processing as described in Dunn’s model. Understanding the 4 basic patterns of sensory processing enables providers to interpret children’s behaviours, and therefore tailor activities and interventions to support children to participate in everyday life. This evidence supports the concept of applying sensory processing knowledge within everyday life.

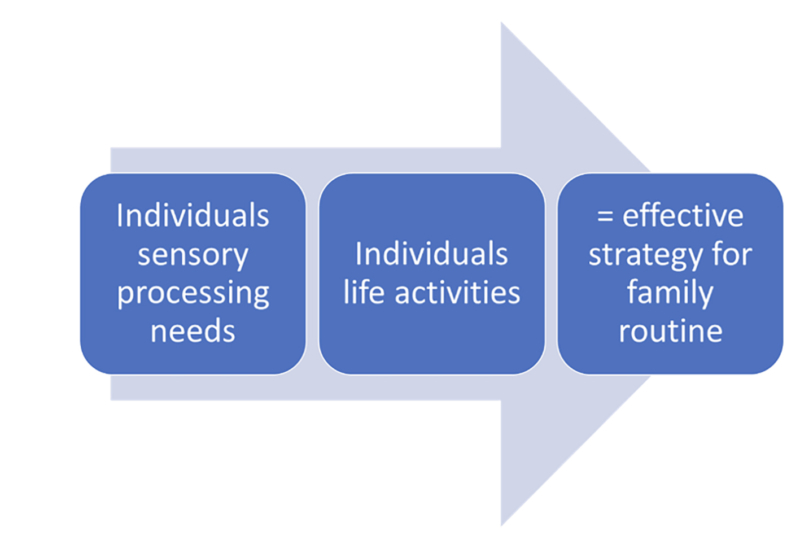

Bridging the gap on supporting everyday routines and ADL’s

Therefore, therapists consult with families to identify the challenging routines for the individuals they work with, and construct strategies in order to adjust daily routines so that they accommodate the individual’s needs, while allowing them to continue to participate in life activities.

When families and providers are able to understand the meaning of the individual’s behaviour from a sensory processing perspective, they can create a more “sensory friendly” environment for them, and by doing so, increase the chances for the person to manage more situations successfully.

Identify sensory needs/ challenges when planning intervention:

- Encouraging family members to keep a diary to determine what the individual may be seeking or avoiding in the senses.

- Think about the Environment at Bath time in relation to Sensory Processing:

- Is there carpet on the floor? Or mats? The noise in the bathroom may echo, they may not like the sound of the running water. Are there bright lights? Is there relaxing music? Are items they need clearly places and accessible?

- Think about the bath time build up:

Before bath time, do activities that provide deep touch input as this is always calming and grounding. The upset before getting in the bath could be to do with getting undressed – this could be to do with temperature. Make sure the room is the right temperature. Let them test the water with their fingers. Again, do deep pressure touch before washing and during the task with shampooing and drying. Make the transition from getting undressed and into the bath as quick and smooth as possible. Make sure the towel and pjs are the right texture for them. - Think about during bath time:

During bath time give them control by letting them choose the sponge/ soap. Try letting them see what is happening in a mirror. If they do not like the water in their eyes have goggles or a towel so they can dry their eyes.

Standardised assessments such as the Sensory Processing Measure or Sensory Profile

- Sensory Processing Measure, Home forms (SPM; 5-12:11; Parham, Ecker, Kuhaneck, Henry, Glennon 2007)

- Sensory Profile 2, Home forms (SP2; 3-14:11; Dunn 2014)

Task Analysis

- Models (PEO Model)

The PEO Model: Occupational performance shaped by the interaction between person, environment, and occupation. Therefore, this model can be viewed as an assessment tool to understand and analyse problematic areas that affect clients’ occupational performance or, as an intervention tool, to improve clients’ occupational performance.

- Sensory Integration Frame of Reference

The Sensory Integration (SI) frame of reference focuses on the interaction between the sensory systems. These outcomes eventually lead to successful participation in daily occupations. Interventions using the SI frame of reference include use of therapeutic equipment to provide children with various sensory opportunities. Sensations are provided in a structured environment, graded to a greater or lesser intensity depending on the needs of each child.

- Considering strategies for bathing in child’s sensory diet

An individualised programme based on controlled sensory input to allow better engagement in the environment.

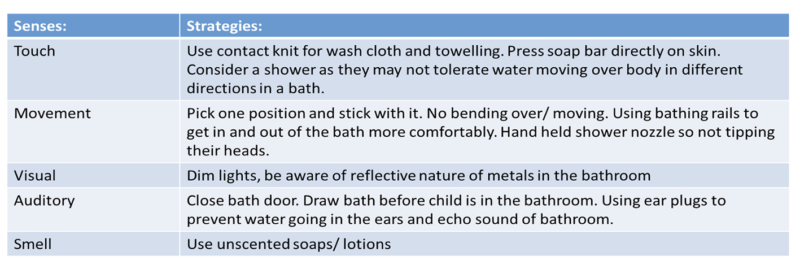

Sensory needs and challenges in a bathing context

- Impaired balance and distress stepping into the bath due to poor vestibular/ proprioceptive processing.

- Difficulties adjusting to changes in water temperature due to tactile modulation difficulties.

- Aversive response to components of bathing and showering: the feel of being showered, having water poured over the head, being wiped with a towel due to tactile hypersensitivity. This could manifest as avoidance, fear or lashing out.

- Aversive response to tipping the head backwards and forwards when washing hair, due to gravitational insecurity.

- Fear of the water.

- Distress over the water being too hot, cold, high, or low.

- Disorientation from being in a small, confined space.

- Difficulties maintaining bodily control on slick, glossy surfaces.

- Instability from stepping in and out of the tub.

- Panic over the plughole and all the abnormal sights and sounds that occur once its unplugged.

Strategies for a better bathing experience

Body awareness (proprioception)

- Heavy face cloth/ sponge with pressure strokes to reduce defensiveness

- Wearing a bathing suit in the tub to add pressure

- Use pressure when drying with a towel and wrap child tightly

- Toys that provide heavy work such as squeeze toys or pouring water from a bucket to another

- Heavy work activities prior to bathing- lifting boxes/ carrying groceries/ packing cupboard/ jumping on trampoline.

Strategies for a better bathing experience – Praxis

- Using visual aids to assist with task

- Breaking skills down into small steps – using task analysis

- Model how to complete washing tasks- sequencing (start at the top then work your way down).

- Long handled sponge may make it easier to get to different parts of the body.

- Labelling items to remind the individual which bottle to use first

- Consider how you can make the individual feel safer in the bath- praxis difficulties may result in individual feeling insecure.

- Self-care routine

- Using a timer for knowing how long to wash for

Strategies for a better bathing experience – Movement

- Seeking sensory input: allow individual to jump or run around prior to bath time.

- Over-responsive to sensory input- washing them in a baby bath (if they are small enough), as they this may make them feel more secure. Use a bathmat or bath seat in the bottom of the bath so that the individual is less likely to slip around.

- Using grab bars to feel more secure if balance is difficult.

- Discomfort in changing head position may make it difficult to have their hair rinsed; try a handheld shower or cover their eyes with a face cloth/ foam visor/ goggles and use a jug to pour water over their hair.

- Dry in front of a mirror to increase body map and awareness.

Strategies for a better bathing experience – Touch

- Start with washing the face before getting into the bath/ shower

- Try to be aware of the temperature of water individual prefers.

- Use firm pressure downward on child’s shoulders whilst bathing them as this is calming.

- Massage child with a facecloth, bath mitt or your hands using firm, constant pressure prior to and during bath time, depending on what your child will tolerate. Use pressure and downward strokes.

- Bath paints/ bath crayons/ tactile soaps/ fidgets if seeking sensory input.

- Have items that encourage ‘heavy work’ for the muscles whilst in the shower or bath e.g., pouring water from one container to another/ squeezing sponges

- If water is not tolerated over their bodies, a shower may be better as water moves in a consistent direction.

- Plastic ring to wear over their ears and around their head to keep unpredictable water to run down the face.

- Use the shower sprayer for rinsing, allowing individual to rinse themselves and provide control.

- A rain shower head.

- Using a towel warmer

- Use heavy towels for drying; use firm constant pressure.

- If your child is oversensitive to touch, use a smaller towel which you can direct more easily. Use a firm pressure.

- Resistant activities prior to bath time.

- If your child struggles with a bath, try a shower or vice-versa. The tactile input from a shower may be more difficult for over-responsive children to cope with and tends to be more alerting so you might want to make this part of the morning routine rather than the wind down bedtime routine.

Strategies for a better bathing experience – Auditory

- If the sound of the running water bothers individuals, fill the bath before you taken them into the bathroom.

- Tell your child where you are going to wash him/her to prepare them.

- Use earplugs to minimise noise and water going into the ear.

- Have plenty of fabric—such as towels, curtains, and bathrobes—in the bathroom to soften any sounds that bounce between hard surfaces.

- Play calming music.

- Sing songs.

Strategies for a better bathing experience – Visual

- Allow the individual to look into a mirror whilst in the bath to increase predictability.

- Use waterproof pictures/visual aids to help understand the task and the predictability.

- Dim the bathroom lights/ LED lights/ floating LED lights/ projectors.

- Use a visual timer as an indication of how long the task will take.

What does the research say?

Study 1: Activities of Daily Living, Playfulness and Sensory Processing in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Spanish Study

Yela-González, N; Santamaría-Vázquez, M and Hilario Ortiz-Huerta, J. Activities of Daily Living, Playfulness and Sensory Processing in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Spanish Study.

This study was carried out in 2021. The purposes of the study were to identify whether differences exist between Spanish children with ASD and neurotypical development in relation to Activities of Daily Living (ADL), playfulness, and sensory processing; as well as to confirm whether a relation exists between those areas and sensory processing.

Methods: Forty children, 20 with a diagnosis of ASD and 20 with neurotypical development, were recruited. The measurement tools used were the Paediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI), Test of Playfulness (ToP), and Sensory Processing Measure: based on the theory of sensory integration of Ayres.

The results suggested that children with ASD experience problems of sensory reactivity and those problems are likewise related to difficulties in the performance of ADL.

Likewise, in the study carried out by Case-Smith, Weaver and Fristad, which was an extension of the study been done after evaluating children with ASD and sensory difficulties, they concluded that the group that received occupational therapy treatment obtained better results for self-care, social skills, and functional independence.

As conclusions to this study, it has been pointed out that these children require greater support from their caregivers and modifications to the environment and the use of supportive resources.

Study 2: Occupational Therapy Using a Sensory Integrative Approach:

A Case Study of Effectiveness

Schaaf, Roseann C. and Nightlinger, Kathleen McKeon,(2007). “Occupational therapy using a sensory integrative approach: a case study of effectiveness.”

Case study of 1 child in 2007.

The goal of the study was to prove intervention can improve the child’s ability to process and integrate sensory information as a basis for enhanced independence and participation in daily life activities.

Method:

Based on assessment data, specific goals were developed and reviewed with the child’s mother to assure that the goals were meeting identified areas of concern. Documentation of progress toward goals was collected and charted weekly. A parent interview was conducted during the final month of intervention to obtain input about the child’s past and present occupational concerns and the success of the OT-SI program in meeting his needs. The sensory profile was used to assess the child’s behaviours and his sensory basis. Goals were developed in collaboration with this and the mother. He presented with hypersensitivity that affects his ability to play and complete everyday tasks such as bathing/ teeth brushing and hair brushing.

The results show that the child’s improvements in his ability to tolerate and process sensory input were striking and apparent in the home and the community. His decrease in fear of movement and tactile stimuli set the stage for participation in age-appropriate play, thus enhancing socialization opportunities. During his occupational therapy sessions, he progressed from unwillingness to participate in climbing and movement activities to playfully enjoying such activities. He tolerated oral–sensory stimuli and participated more in hygiene tasks with less fuss.

This case contributes to the evidence for using a sensory integrative approach within occupational therapy, demonstrating, as Ayres (1979) intended. He stated, “If the brain does a poor job of integrating sensations, this will interfere with many things in life. There will be more effort and difficulty, and less success and satisfaction” (Ayres, 1979, p. 7)