Sensory Bathing – theory and approach

Bathing is thought to be an important activity to all of us for the primary purpose of keeping clean and helping us maintain our personal hygiene. The definition from the Bartel Index by Mahoney and Barthel (1965) is;

‘Being able to get in and out of the bath unsupervised and able to wash self’

Therefore, this seems like a straightforward task and more of a process according to Mahoney and Barthel (1965), but is there more to this task and process than what it may first appear, and does it have more meaning and value to those clients that engage in bathing?

Within a study by Mayers (1998) focusing on bathing/showering it was found that there was a discrepancy between the perceived importance of bathing by support staff for their clients and that of the actual client, with the client rating the importance of bathing/showering as significantly higher to them in value than the rating of the support staff’s perception for them. In addition Wright (1960) and Koren (1996) view bathing as a multifaceted activity that has many qualities such as relaxation, wellbeing, thermal stimulation, and pleasure. These aspects should therefore be considered by practitioners when assessing the needs of the client, for it is not only access to the bath and the process of bathing that is important, it is the value and meaning within the ‘doing’ of the activity that can potentially hold the key to unlocking positive health and wellbeing outcomes for individuals.

Sensory processing

Sensory processing is viewed by some as the relationship between difficulties participating in academic and motor learning and difficulties with interpreting sensations from the environment and one’s own body (Bundy & Lane, 2020). Whereas Ayres (2005) defined Sensory Integration as;

‘the organisation of sensory input for use…through sensory integration, many parts of the nervous system work together so that a person can interact with the environment effectively and experience appropriate satisfaction’.

As an occupational therapist, enabling client’s to experience satisfaction is important to facilitate positive health and wellbeing outcomes and each are interlinked to the other, therefore understanding how we can utilise sensory strategies to help clients achieve this state is key.

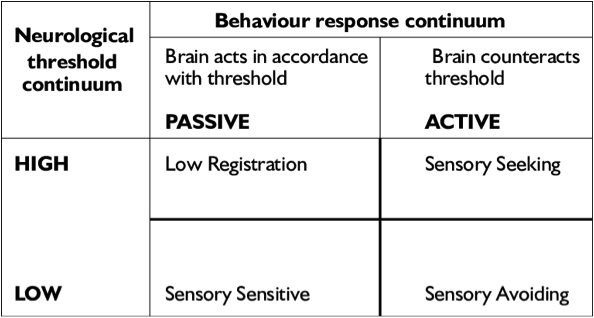

It is important to understand that client’s with sensory processing difficulties are unique and if they have a processing difficulty within one or more of the senses this may result in difficulties modulating the sensory information they receive, a high neurological threshold (hyposensitivity), or a low neurological threshold (hypersensitivity) to stimuli. In each case the strategies and interventions used would look significantly different for a client depending on their sensory needs and neurological threshold; this is an important consideration during the assessment and intervention planning stages for clinicians.

Dunn’s (2007) Neurological Threshold Behaviour Response Continuum.

Sensory processing and bathing

As discussed bathing can have many benefits and values for different reasons to the individual, some of these may lie within the sensory feedback received during bathing or the subsequent impact on the body’s nervous system. Some research has found that having a hot bath before bed can positively influence the body’s circadian rhythm and sleep patterns through the elevation in body temperature, activating the body’s autonomic nervous system, particularly the parasympathetic aspect that is responsible for activating the ‘rest and digestion’ response (Haghayegh et al, 2019).

Those with sensory processing difficulties where they have a high neurological threshold (hyposensitivity) for tactile stimuli such as touch and temperature recognition, means that they may require additional stimulation for registration with the nervous system, to be alert, and to counteract the neurological threshold to achieve the optimum level of arousal. Similarly those with a high neurological threshold for tactile stimuli may seek out additional sensation in this area in order to counteract the high neurological threshold and self-regulate their own levels of arousal and behaviour (Dunn, 2007). When relating to Ayres (2005) sensory integration theory, bathing may actually be used as a method of a strategic intervention, stimulating the tactile system through touch and temperature from the water; this may help modulate an individual’s level of arousal and behaviour by providing the sensory input they are seeking.

It is also important to be aware of the risks that a bath could have for someone with a low neurological threshold (hypersensitivity) to tactile input, such as over responsiveness. However if used as part of a graded approach/intervention by a sensory integration therapist/ experienced Occupational Therapist this may help to develop reduced sensitivity to tactile stimuli and to the activity of bathing over time.

Deep pressure is a sensory integration intervention involving the tactile system that can be used to help to calm and organise an individual’s nervous system, whilst regulating levels of arousal and behavioural outcomes by activating deep tactile receptors in the body (SI Network, 2021). The pressure of the water alone may not be enough to do this but a face cloth or small towel can be used to apply gentle deep pressure to the body to activate the parasympathetic nervous system which promotes a ‘rest and digest’ calming response to the body. Massaging soap into the body can also be used as an activity for deep pressure application; equally after a bath when the individual is getting dried firm rubbing with the towel may also have the same effect. Self-regulation and self-application of any interventions should always be promoted first to maximise an individual’s independence within this area before passive interventions are used.

Showering is an activity that can often trigger an over responsive reaction to those with a low neurological threshold (hypersensitive) tactile system. If there is a client that is displaying concerning reactions or behaviours during showering it may be worth considering hypersensitivity to tactile stimuli as part of the clinical reasoning process for the clinician; a broad consideration of all areas of tactile input is required as part of the assessment process.

Strategies

Exploration of water at the earliest opportunity is important for those that maybe hypersensitive to it, thereby providing the client the opportunity to develop a reduced sensitivity to activities involving water that are integral to daily life such as personal care. Using a graded approach for interventions is important to build up the tolerance of a client over time, activities exposing small parts of the body to the water first, such as a finger or hand, then gradually building up exposure to an arm, and encompassing more of the body over the weeks/months will be beneficial to support this. Interventions should be graded and client centred, being guided by the individual is important to not cause any unnecessary distress throughout the process.

A bath can provide a calm space when used in combination with the correct levels of audio and visual stimulation for the client’s sensory needs to promote rest and relaxation which can help with energy levels and self-regulation; when a client has low energy levels or a lack of sleep it can be harder to self-regulate effectively.

While enabling and empowering people with disabilities to carry out valued occupations and activities, including bathing, occupational therapists are urged to be as client centred as possible (Christiansen and Baum 1997, Neistadt and Crepeau 1998), being mindful that bathing is a personal activity in which people like to be independent, need to be assured of privacy and need to have their dignity maintained. All sensory interventions are bespoke and tailored to an individual’s sensory profile, it is important to note that any assessment and intervention for those with sensory needs should be carried out by a suitably trained sensory integration therapist or occupational therapist experienced in this area.

References

Ayres, A. J. (2005). Sensory integration and the child (25th Anniversary Edition). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Bundy, A., & Lane, S. J. (2020). Sensory Integration: Theory and Practice (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis. Koren L (1996) Undesigning the bath. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press.

Christiansen C, Baum C (1997) Occupational therapy: enabling function and well-being. Thorofare, NJ: Slack.

Dunn, W. (2007). Supporting children to participate successfully in everyday life by using sensory processing knowledge. Infant and Young Children, 20, 84-101.

Haghayegh, S., Khoshnevis, S., Smolensky, M. H., Diller, K. R., Castriotta, R. J. (2019). Before-bedtime passive body heating by warm shower or bath to improve sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 46, 124-135.

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW (1965) Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Rehabilitation, Feb, 61-65.

Mayers CA (1998) An evaluation of the use of the Mayers’ Lifestyle Questionnaire. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61(9), 393-98.

Neistadt ME, Crepeau EB (1998) Introduction to occupational therapy. In: ME Neistadt, EB Crepeau, eds. Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 5-12

Wright L (1960) Clean and decent. London: Butler and Tanner.

Sensory Integration Module 1 (2021) SI Network. www.sensoryintegrationeducation.com